Health & Wellness • 8 min read

The Key Data

• Endodontists saw 2x (100% increase) in cracked teeth cases by September 2020 vs. 2019

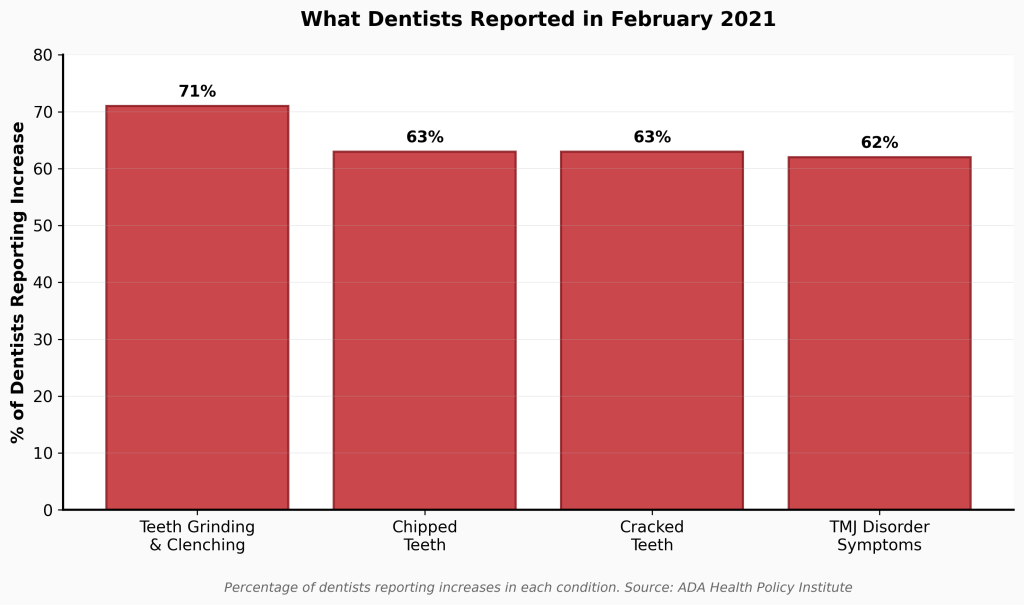

• 71% of dentists reported increased teeth grinding and clenching (February 2021)

• 63% of dentists reported increased chipped teeth (February 2021)

• 63% of dentists reported increased cracked teeth (February 2021)

• 62% of dentists reported increased TMJ disorder symptoms (February 2021)

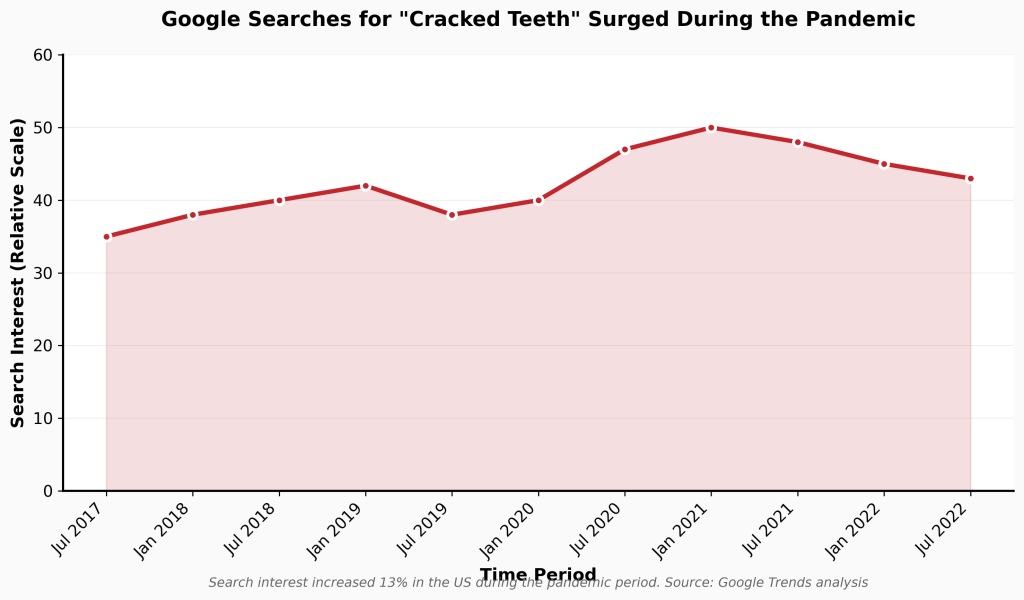

• Google searches for “cracked teeth” increased 13% in the US during pandemic period (2020-2021)

• 49% of endodontists already reported seeing more cracked teeth by 2015 (pre-pandemic baseline)

The Key Facts

The Crisis: Cracked teeth doubled between 2019 and 2020. By February 2021, 71% of dentists reported patients grinding their teeth more than ever before.

Who’s Affected: Primarily ages 40-60, especially males. This is the demographic with decades of dental work, peak life stress, and aging teeth that have lost flexibility.

The Five Main Causes:

- Pandemic stress triggered unconscious clenching (250+ psi of force vs. normal 68 psi)

- Poor home office posture (“tech neck”) changes how teeth meet, causing 2,000+ grinding events per day

- Aging population keeping teeth longer—but 70-year-old teeth are brittle and crack-prone

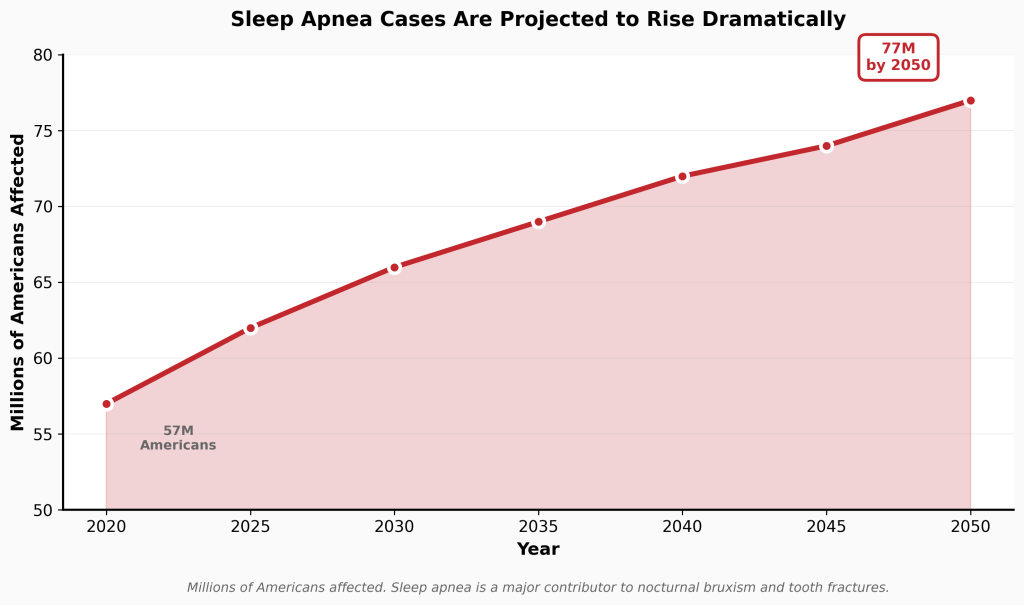

- Undiagnosed sleep apnea (77 million Americans by 2050) causes nightly tooth grinding to maintain breathing

- Hard “healthy” foods like almonds act as wedges on already-weakened teeth

The Bottom Line: This isn’t just about dental health. Cracked teeth are a symptom of how modern Americans live—stressed, poorly postured, sleep-deprived, and aging with dental work that wasn’t designed to last 50+ years. The problem isn’t going away.

Something strange started happening in dental offices around 2020. Patients who’d never had problems before were showing up with cracked molars. Teeth were splitting in half while people ate bagels or granola. Root canals that should have lasted decades were failing. The pattern was unmistakable, and dentists across the country couldn’t ignore it anymore.

By September 2020, endodontists—the specialists who treat damaged teeth—were seeing twice as many cracked teeth as they had the year before. Not a gradual increase. A doubling. In six months.

The American Dental Association ran surveys. Seventy-one percent of dentists reported patients grinding their teeth more than ever. Sixty-three percent were seeing more cracks and chips. Something fundamental had shifted.

But this wasn’t actually about the pandemic. COVID just accelerated a problem that had been building for years, a collision of factors that most people never think about until they hear that sickening crack while biting down on something innocuous.

The Data Paints a Clear Picture

Looking at Google search trends tells you what people were experiencing at home, before they even got to a dentist. Between 2017 and 2022, searches for “cracked teeth” jumped 13% in the United States during the pandemic period. People were noticing pain when they bit down, sensitivity to cold, sudden jolts of discomfort. They were looking for answers online because dental offices were closed or operating at limited capacity.

Search interest increased 13% in the US between 2020-2021. Data source: Google Trends analysis

The clinical data backed this up. A February 2021 survey by the ADA’s Health Policy Institute found that stress-related dental conditions had become the dominant complaint in dental practices. The numbers were stark.

Percentage of dentists reporting increases in each condition. Source: ADA Health Policy Institute

Here’s what makes this significant: tooth fractures aren’t like viral infections. They don’t spread exponentially through a population. A doubling of cases in such a short window means something environmental or behavioral changed suddenly and dramatically for millions of people at once.

Who’s Getting Hit Hardest

The 40-to-60 age group took the brunt of it. These are people who’ve accumulated decades of dental work—fillings from childhood, maybe a crown or two, possibly a root canal. Their teeth have structural vulnerabilities. Add unprecedented stress, and those weaknesses become fracture points.

By 2021, males aged 40-60 and over-60 showed particularly sharp increases in cracked teeth. This demographic shift likely reflects both delayed care-seeking behavior and the compound effects of stress on people managing careers, families, and aging parents simultaneously.

A study published in the Journal of Endodontics tracked this pattern. In 2020, the 40-60 age bracket showed significant increases. By 2021, the spike extended specifically to males in both the 40-60 and over-60 groups. Men tend to ignore dental pain longer. When they finally come in, the damage is often catastrophic.

Five Factors Driving the Epidemic

1. The “COVID Clench” Was Real

Dentists gave it a name: the COVID Clench. When you’re anxious, your body tenses. Your shoulders rise. Your jaw locks. Most people have no idea they’re doing it.

Normal chewing generates about 68 pounds per square inch of force. Stress-induced grinding? Over 250 pounds per square inch. Worse, functional chewing applies vertical force, which teeth can handle. Grinding creates horizontal shear forces that enamel wasn’t designed to withstand.

Teeth don’t usually break from a single traumatic event. They fail through fatigue. Repetitive sub-critical loads create microcracks that propagate slowly until one normal bite—on a piece of toast, say—exceeds the tooth’s remaining structural capacity. Snap.

The pandemic compressed years of this fatigue damage into months. People were clenching all day at their laptops. Grinding at night worrying about layoffs, sick relatives, remote schooling. The intensity and frequency were unprecedented.

2. Your Home Office Is Breaking Your Teeth

This one surprised researchers. The connection between posture and tooth damage isn’t obvious until you understand the biomechanics.

When your head tilts forward—”tech neck”—it doesn’t just strain your cervical spine. For every inch your head moves forward from neutral alignment, you add roughly 10 pounds of force to your neck. At a three-inch forward carriage, your neck is supporting 42 pounds instead of 12.

That tension pulls on the muscles connecting your skull to your jaw. The sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles tug your mandible backward and down. Now when you close your teeth, they don’t meet where they’re supposed to. Your back molars hit first. Your jaw has to slide forward from this premature contact point to fully close.

You swallow about 2,000 times a day. Every single time, if you have tech neck, your teeth are grinding past each other horizontally. It’s like dragging a knife across a stone. Eventually, the cusps wear down or fracture.

Studies using computerized bite analysis confirmed this. People with forward head posture show asymmetric bite forces and longer occlusion times. Instead of all teeth hitting simultaneously and distributing force evenly, one or two molars take the entire 250+ psi hit.

3. Success Has Created a New Problem

Americans are keeping their natural teeth longer than ever before. That’s a public health triumph. In 1999, nearly 30% of adults over 65 had lost all their teeth. By 2020, that number dropped to 13%. Fluoride in water, better dental care, more awareness—it all worked.

But here’s the paradox: a 70-year-old tooth is fundamentally different from a 20-year-old tooth. As teeth age, their internal structure changes. The microscopic channels in dentin (the layer beneath enamel) fill with mineral deposits. This makes teeth more cavity-resistant but also more brittle. They lose moisture and flexibility.

Think of the difference between a green tree branch and a dry one. The green branch bends. The dry one snaps. An aging tooth has undergone millions of chewing cycles and decades of thermal stress—hot coffee followed immediately by ice water, over and over. All of that accumulates.

We now have more teeth at risk because we’re keeping them longer. And those teeth are more vulnerable because they’re older. The “silver tsunami” of aging Baby Boomers who retained their dentition has created a massive inventory of fragile teeth.

4. Sleep Apnea Is Destroying Teeth

For years, dentists thought bruxism (teeth grinding) was caused by stress or bite problems. New sleep research has revealed something more disturbing: in many patients, grinding is your body’s desperate attempt to breathe.

When you have obstructive sleep apnea, soft tissue in your throat collapses during sleep and blocks your airway. Your brain detects the oxygen drop and triggers a micro-arousal. To reopen the airway, your jaw muscles contract violently, thrusting your mandible forward. That contraction is grinding. Your teeth are the collateral damage in your body’s fight for oxygen.

About 26% of adults aged 30-70 have at least mild sleep apnea. By 2050, that number is projected to hit 77 million Americans—a 35% increase from 2020. That’s 77 million people whose teeth are being ground down every night as a survival mechanism.

Millions of Americans affected. Sleep apnea is a major contributor to nocturnal bruxism and tooth fractures.

Studies now show a statistically significant relationship between OSA and tooth fractures, particularly in patients over 40. When a middle-aged patient comes in with a split molar, a thick neck, and a history of snoring, dentists increasingly recognize this isn’t just dental—it’s respiratory.

5. Healthy Eating Has an Unexpected Cost

The rise of paleo, keto, and plant-based diets has been great for overall health. Less great for teeth.

U.S. almond consumption has grown 5.5% annually since 2000. Between 2023 and 2024 alone, it jumped 6.5%. Raw almonds, granola clusters, unpopped popcorn kernels—these are mechanically hazardous. They’re harder than most foods people traditionally ate.

When you bite down on an almond, it acts as a fulcrum. The entire force of your bite concentrates on a tiny point of tooth cusp. If that tooth has a microfracture or a large filling, the nut becomes a wedge that drives the segments apart. One wrong bite can split a compromised tooth completely.

Research has identified “eating coarse foods” and “chewing hard objects” as independent risk factors for cracked teeth. Ice chewing—often a symptom of iron deficiency anemia—is particularly destructive. Ice subjects teeth to extreme cold (contraction) followed by body temperature (expansion). This thermal cycling creates stress fractures in enamel. And unlike food that softens as you chew it, ice remains rigid until it shatters. The impact force often exceeds what tooth enamel can handle.

Old Dental Work Is a Ticking Clock

If you’re in your 40s or 50s, there’s a good chance you have metal amalgam fillings from the 1970s or 80s. Those “silver fillings” don’t bond to tooth structure. They’re held in place by mechanical retention—undercuts drilled into the tooth that create a lock-and-key fit.

Here’s the problem: amalgam expands and contracts with temperature at a different rate than natural tooth structure. Decades of hot coffee followed by cold water create a slow-motion wedging effect. The metal pushes outward when hot, then contracts when cold, but the tooth doesn’t move at the same rate. Over time, this mechanical stress propagates cracks from the filling outward toward the surface.

Studies confirm that amalgam restorations are associated with specific fracture patterns, especially when wear facets are present. Modern composite resins bond to teeth and can actually reinforce the structure, but millions of Americans still have those old amalgam fillings acting as internal wedges.

This creates what dentists call the “death spiral” of a tooth:

- Small cavity in your teens, small filling

- Filling fails in your 30s, gets replaced with a larger one

- By your 40s or 50s, remaining tooth structure is thin and compromised

- Life stress triggers grinding

- Tooth fractures

The 40-60 demographic is at the epicenter of this epidemic because they’re at exactly this stage. Minimal structural integrity meets maximal life stress.

What This Means Going Forward

The cracked tooth has replaced the cavity as the defining challenge of adult restorative dentistry. That’s not hyperbole. The American Association of Endodontists stated in 2019 that cracked teeth must now be included in “almost every differential diagnosis of tooth pain.”

This isn’t going to reverse. The factors driving it aren’t temporary:

- Remote and hybrid work continues, perpetuating posture problems

- America’s population keeps aging, retaining more brittle teeth

- Sleep apnea prevalence is rising with obesity rates

- Economic and social stressors remain high

- Dietary trends toward harder, “healthier” foods continue

The good news? Recognition is growing. Dentists are screening more patients for sleep apnea. Night guards (occlusal splints) are being prescribed preventively rather than reactively. There’s increased awareness about the connection between posture and bite problems.

Treatment outcomes have also improved. Historically, deep cracks involving the root meant extraction. Recent studies show that if treated with a crown to bind the segments together—and root canal therapy if the nerve is involved—survival rates range from 82% to 96% over two to four years. The prognosis depends heavily on periodontal health; if a crack has created a deep pocket alongside the root, success drops significantly.

The incidence of cracked teeth is up, but tooth loss from cracks may not rise proportionally—if patients seek timely care. Early intervention matters tremendously. By the time a crack is symptomatic, structural damage is often extensive.

A Window Into How We’re Living

What makes this story compelling isn’t just the dental statistics. It’s what those statistics reveal about modern American life.

We’re stressed to the point that our bodies are literally breaking down. We’re working in environments that weren’t designed for eight-hour days (kitchen tables, couches, beds). We’re eating foods that our teeth—evolved for softer diets—struggle to handle. We’re living longer but not necessarily in ways that support the longevity of our bodies. And millions of us can’t breathe properly at night, a problem that manifests in destroyed dentition.

Teeth are canaries in the coal mine. They show wear patterns, stress indicators, and systemic health issues long before other symptoms appear. The epidemic of cracked teeth is less about oral hygiene and more about how we’re living. The lockdowns of 2020 just made the underlying fragility impossible to ignore.

Dentists have shifted from thinking about caries prevention to thinking about load management. The question is no longer “how do we prevent holes in teeth?” but “how do we prevent excessive forces on teeth?” That’s a fundamentally different paradigm—one that requires addressing stress, sleep, posture, and lifestyle factors far beyond the mouth.

The surge in broken teeth is real, documented, and continuing. What happens next depends on whether we treat it as isolated dental problems or as symptoms of larger systemic issues that need addressing.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I know if I’m grinding my teeth?

Many people don’t realize they’re grinding. Common signs include waking up with jaw soreness, headaches at the temples, unexplained tooth sensitivity to cold, a partner mentioning nighttime grinding sounds, or noticing your teeth look shorter or more worn. Your dentist can spot telltale wear patterns during exams.

Can a cracked tooth heal on its own?

No. Unlike bones, teeth cannot regenerate or heal cracks. Once a crack forms, it will only propagate further under continued stress. Small cracks can be monitored, but most eventually require treatment—typically a crown to bind the tooth segments together and prevent complete fracture.

Is a night guard worth it?

Absolutely, especially if you’re in the high-risk age bracket (40-60) or have existing dental work. A custom-fitted night guard from your dentist distributes bite forces evenly and prevents the 250+ psi grinding that cracks teeth. Over-the-counter guards can work but often don’t fit properly. Think of it as insurance—spending $300-600 now beats a $2,000+ crown and root canal later.

What’s the connection between posture and tooth damage?

When your head tilts forward (tech neck), it pulls your jaw backward through connected muscles. This changes where your teeth meet when you close your mouth. Instead of even contact, your back molars hit first and hardest. You swallow roughly 2,000 times per day—each time creating a grinding motion that wears down those molars. Fix your posture, reduce the grinding.

Should I get tested for sleep apnea?

If you snore loudly, wake up gasping, feel exhausted despite sleeping 7-8 hours, or have unexplained tooth wear, yes. Sleep apnea doesn’t just crack teeth—it increases risk of heart disease, stroke, and diabetes. Many dentists now screen for it because they see the dental damage first. A simple home sleep test or sleep study can diagnose it.

Are almonds really that bad for teeth?

Almonds themselves aren’t the enemy—the problem is biting down on a hard object when you have pre-existing microcracks or large fillings. The almond acts as a fulcrum, concentrating all your bite force on one small point. If you love almonds, consider sliced instead of whole, or soak them to soften. Same goes for popcorn kernels, ice, and hard granola.

What should I do if I crack a tooth?

Call your dentist immediately, even if there’s no pain. Pain often doesn’t appear until the crack reaches the nerve. Avoid chewing on that side. Don’t use temporary dental cement from drugstores on cracks—it can trap bacteria. If a piece breaks off, save it and bring it to your appointment. Time matters; the sooner a crack is treated, the better the prognosis.

Will my dental insurance cover treatment for cracked teeth?

Usually, yes—but it depends on the treatment needed. Crowns are typically covered at 50% after deductibles. Root canals are covered similarly. However, if the tooth requires extraction and an implant, that can run $3,000-5,000+ with insurance covering only a portion. Check your specific plan’s coverage for “major restorative work.”

Is this problem really getting worse, or are dentists just better at detecting it?

It’s genuinely getting worse. While diagnostic tools have improved, the data shows dramatic increases in short timeframes that can’t be explained by detection alone. A 100% increase in six months (2019 to 2020), Google search spikes, and consistent reports across thousands of independent practices all point to a real surge, not just better awareness.

Can stress really cause that much physical damage?

Yes. Chronic stress activates your sympathetic nervous system, increasing muscle tension throughout your body—including jaw muscles. This isn’t conscious behavior; it’s physiological. Studies show stressed individuals can generate 3-4 times normal biting force without realizing it. Over months or years, that sustained pressure creates cumulative damage that eventually manifests as fractures.

This analysis synthesizes data from the American Association of Endodontists, American Dental Association Health Policy Institute, National Dental Practice-Based Research Network, and multiple peer-reviewed studies published between 2015-2025.

The following is the full research report:

~~~

The Fracture Pandemic: An Epidemiological, Biomechanical, and Sociological Analysis of the Surge in Cracked Dentition (2015–2025)

Abstract

Over the decade spanning 2015 to 2025, the United States dental healthcare system recorded a statistically significant and clinically alarming rise in the incidence of cracked, fractured, and broken teeth. While dental caries and periodontal disease have historically constituted the primary workload for restorative dentistry, the “cracked tooth” has emerged as a dominant pathology, characterized by complex etiology and challenging diagnostic parameters. This report synthesizes data from the American Association of Endodontists (AAE), the American Dental Association (ADA) Health Policy Institute, the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network (NDPBRN), and independent clinical studies to construct a comprehensive analysis of this phenomenon. The findings indicate that the surge is not attributable to a single pathogen or cause but is the result of a convergence of biopsychosocial factors: the acute stressors of the COVID-19 pandemic, the ergonomic consequences of remote work (“tech neck”), the biomechanical vulnerabilities of an aging population retaining dentition, the rising prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing, and shifts in dietary consumption patterns. This document serves as an exhaustive examination of the data, theories, and clinical realities defining this silent epidemic.

1. Introduction: The Changing Face of Dental Pathology

The landscape of oral health in the United States has undergone a profound transformation in the early 21st century. For decades, the primary enemy of the natural dentition was bacterial acid demineralization—tooth decay. However, as fluoride usage became ubiquitous and oral hygiene education improved, the prevalence of smooth-surface caries in adults stabilized. In its place, a mechanical pathology began to rise: the structural failure of the tooth unit itself.

The “cracked tooth” is often described as an orphan diagnosis. Unlike a cavity, which is easily visible on a radiograph, a crack is often invisible, symptomatic only under specific loading conditions, and devastating in its progression. By 2019, the diagnosis of cracked teeth had become so prevalent that the American Association of Endodontists (AAE) noted it must be included in almost every differential diagnosis of tooth pain.1

The period from 2020 to 2025 accelerated this trend, compressing what might have been decades of wear and tear into a few short years of intense physiological and psychological stress. This report analyzes the trajectory of this increase, dissecting the localized spikes in incidence and the broader, secular trends that underpin the fragility of the modern American dentition.

2. Epidemiology: Quantifying the Surge (2015–2025)

To understand the magnitude of the issue, one must examine the epidemiological data stratified by time period, comparing the pre-pandemic baseline with the acute crisis phase and the subsequent “new normal.”

2.1 The Pre-Pandemic Baseline (2015–2019)

The rise in cracked teeth did not begin with SARS-CoV-2. It was a pre-existing condition of the American population that was exacerbated by the crisis. In 2015, the AAE Special Committee on the Methodology of Cracked Tooth Studies conducted a landmark survey of endodontists—specialists who treat the dental pulp and are often the “last line of defense” for a cracked tooth.

The survey revealed that 49% of the 941 endodontists surveyed had already observed an increase in cracked teeth and vertical root fractures compared to previous decades.1 This suggests that by the mid-2010s, structural factors within the population were already reaching a tipping point. The causes cited during this period were primarily mechanical and demographic: an aging population and the life-cycle of large amalgam restorations placed in the 1970s and 1980s.

2.2 The Pandemic Inflection Point (2020–2021)

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 acted as a massive systemic stress test on the oral health of the nation. The data from this period is stark, indicating a correlation between societal instability and parafunctional oral habits that is nearly unprecedented in dental literature.

2.2.1 Specialist Case Volume

By September 2020, six months into the pandemic, endodontists reported managing twice as many cracked teeth as they had in the previous year.1 This 100% increase in case volume within such a short window is statistically anomalous for non-infectious dental pathology. Unlike a viral outbreak which spreads exponentially, tooth fractures are typically linear in their incidence. A doubling of cases suggests a sudden, population-wide change in environmental or behavioral conditions.

2.2.2 General Practice Surveillance

The American Dental Association’s Health Policy Institute (HPI) initiated a series of tracking polls to gauge the impact of the pandemic on dental practices. These polls served as a barometer for the “stress loads” of the population.

- Fall 2020: Just under 60% of dentists reported an increase in stress-related conditions.

- February 2021: The numbers climbed significantly as the pandemic fatigue set in.

- 71% of dentists reported an increase in the prevalence of teeth grinding and clenching (bruxism).2

- 63% reported an increase in chipped teeth.2

- 63% reported an increase in cracked teeth.2

- 62% reported an increase in temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder symptoms (headaches, jaw pain).2

This data indicates a high concordance between the subjective reports of dentists and the objective increase in procedural volume. The “stress phenotype” had become the dominant presentation in the dental chair.

2.3 Infodemiological Verification: What Patients Search For

Clinical data can sometimes be skewed by access to care; for example, if only emergency cases are seen, the rate of severe pathology appears artificially high. To verify that these clinical observations reflected a broader population-level trend, researchers utilized infodemiology—the study of determinants and distribution of health information on the internet.

A study analyzing Google Trends data from July 2017 to July 2022 compared search volumes for “Cracked Teeth” in the United States and the United Kingdom.

| Metric | United States (Median Score) | United Kingdom (Median Score) | Statistical Significance |

| Pre-COVID Score | 38 (IQR 32-45) | 25 (IQR 17-33) | – |

| COVID Period Score | 43 (IQR 37-53) | 28 (IQR 18-42) | p < 0.001 |

| Increase | +13% | +12% | Significant |

Data Source: 3

The analysis confirmed a significant increase in search volume (+13% in the US) during the pandemic. This correlates strongly with the ADA and AAE clinical reports, suggesting that patients were experiencing symptoms at home—pain to biting, sensitivity to cold—and seeking information online. This behavior was likely exacerbated by the initial closures of dental offices, which delayed treatment and allowed minor cracks to propagate into symptomatic fractures requiring urgent search for remedies.

2.4 The Discrepancy of Data: The European Divergence

It is crucial to note that the “fracture pandemic” appears to be more pronounced in the United States than in some other regions, or at least, the data is more heterogeneous. A retrospective study conducted in a general dental practice in Bavaria, Germany, from 2018 to 2023, found no significant differences in fracture incidence between pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic periods.4

Table: Incidence of Incomplete Fractures (Cracks) in Bavarian Study 4

| Year | Total Patients | Incomplete Fractures (n) | Percentage |

| 2019 (Pre) | 1622 | 8 | 0.49% |

| 2020 (Pan) | 1392 | 11 | 0.79% |

| 2021 (Pan) | 1551 | 14 | 0.90% |

| 2022 (Post) | 1925 | 17 | 0.88% |

While there is a slight upward trend (from 0.49% to 0.90%), the study authors concluded the difference was not statistically significant. This stands in sharp contrast to the US data showing a doubling of cases. Several theories explain this divergence:

- Referral Bias: The German study was in a general practice. US data relies heavily on endodontists (specialists). During the pandemic, general dentists in the US often deferred complex procedures to specialists, artificially inflating specialist volume while keeping general practice volume flat.

- Psychosocial Differences: The societal response to the pandemic, including the levels of economic anxiety and the structure of social safety nets, differed between the US and Germany. Higher baseline anxiety in the US population regarding healthcare access and employment may have manifested as more severe bruxism.

- Dietary Differences: As detailed in later sections, American consumption of hard foods (nuts, ice) may differ from European norms.

Conversely, a study in Romania found that the number of vertical root fractures tripled during the pandemic (from 0.53% to 1.53%), aligning more closely with the US experience.5 This suggests that while regional variations exist, the trend toward increased fractures was widespread where stress levels were high.

2.5 The Lag in Insurance Claims Data

Interestingly, major insurance carriers did not immediately report a surge in claims matching the clinical anecdotes. Delta Dental, analyzing claims data from 2017 to 2021, noted that “claims data could not confirm anecdotal reports of an increase in cracked or fractured teeth”.6

This discrepancy reveals a limitation in administrative data versus clinical reality. A “cracked tooth” does not have a unique, universally used billing code in the early stages.

- Coding Ambiguity: A dentist might bill a crown (D2740) for a cracked tooth, or a filling (D2335), or an extraction (D7140). The diagnosis “cracked tooth” is often the reason for the procedure, but the procedure code is generic.

- The “Watch” Phase: Many cracks are diagnosed and monitored. These generate no claims until they fail catastrophically.

- Extraction Bias: If a tooth is split and extracted, it appears in the data as an extraction, indistinguishable from an extraction due to decay or periodontal disease.

Therefore, the rise in cracks is often “hidden” in the claims data within the volumes of crowns and extractions, only becoming visible through provider surveys and specific keyword analyses in clinical notes.

3. The Biopsychosocial Mechanism: Stress, Bruxism, and the “COVID Clench”

The primary driver of the spike in broken teeth from 2020 to 2025 is the physiological manifestation of psychological stress, colloquially termed the “COVID Clench.” The masticatory system is a primary outlet for somatic stress release, and the unprecedented anxiety levels of the last half-decade have manifested as destructive occlusal forces.

3.1 The Neurobiology of Stress-Induced Parafunction

The connection between anxiety and the masticatory muscles is mediated by the limbic system and the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. When an individual experiences stress, the sympathetic nervous system is activated.

- Muscle Spindle Activation: Sympathetic outflow increases gamma efferent activity to the muscle spindles of the masseter, temporalis, and medial pterygoid muscles. This increases the resting tone of the muscles.

- Subconscious Clenching: This heightened tone leads to diurnal bruxism (daytime clenching). Unlike nocturnal bruxism, which is rhythmic, diurnal bruxism is often a sustained, isometric contraction. Patients are often unaware they are doing it until pain develops.

- Force Magnitude: The average human bite force during functional chewing is approximately 68 lbs/sq inch. During parafunctional bruxism events, forces can exceed 250 lbs/sq inch. Furthermore, functional chewing applies vertical forces, which teeth are designed to handle. Bruxism often involves horizontal or shear forces, which are highly destructive to the crystalline structure of enamel.

3.2 The “Fracture Fatigue” Phenomenon

Teeth are quasi-brittle materials. They generally do not fail due to a single traumatic event (unless it is an impact injury) but rather through fatigue failure.

- Initiation: Repetitive sub-critical loads (chronic clenching) initiate micro-cracks in the enamel, typically at the cervical margin or the base of a cusp.

- Propagation: Once a micro-crack forms, stress concentration occurs at the crack tip. The “stress intensity factor” increases as the crack deepens.

- The Wedging Effect: Continued clenching acts as a wedge. If a restoration (filling) is present, the different elastic moduli of the tooth and the filling material create internal tension.

- Catastrophic Failure: Eventually, a standard bite force (e.g., chewing a bagel or a nut) exceeds the remaining structural integrity of the tooth, resulting in a sudden cusp fracture or split tooth.

The “pandemic surge” was essentially a compression of this timeline. Years of fatigue damage were condensed into months due to the intensity and frequency of stress-induced clenching during lockdowns and the subsequent economic uncertainty.

3.3 Demographics of the “Stressed Tooth”

The burden of this stress-induced damage was not distributed equally. Research published in the Journal of Endodontics comparing data from 2019 to 2021 identified specific vulnerabilities 1:

- 2020: A significant increase in the incidence of cracked teeth in the 40–60 age group.

- 2021: An increase specifically in males in the 40–60 and over-60 age groups.

Interpretation: This demographic specificity likely correlates with the populations most affected by economic instability, career disruption, and health anxieties during the crisis. The 40–60 cohort often carries the dual burden of caring for children and aging parents (“the sandwich generation”), creating a peak stress environment. The shift to males in 2021 may reflect delayed care-seeking behavior; men may have ignored early symptoms in 2020, presenting with catastrophic fractures only when pain became unbearable in 2021.

4. The Ergonomic Crisis: “Tech Neck” and Occlusal Disharmony

A less obvious but highly significant contributor to the rise in cracked teeth is the massive shift toward remote work and the resulting deterioration of posture. This phenomenon links the cervical spine to the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), creating a kinetic chain of dysfunction.

4.1 The Work-From-Home (WFH) Experiment

The pandemic forced millions of Americans into makeshift home offices. Lacking ergonomic furniture, workers utilized sofas, kitchen tables, and beds. This led to a prevalence of Forward Head Posture (FHP), often called “Tech Neck.”

- Biomechanics of FHP: In a neutral position, the head weighs 10-12 pounds. For every inch the head moves forward from neutral alignment, the load on the cervical spine increases by approximately 10 pounds. At a 3-inch forward carriage, the neck is supporting 42 pounds of force.7

4.2 The Sternocleidomastoid (SCM) and Trapezius Connection

The muscles that control the head and neck are inextricably linked to the muscles of the jaw.

- Electromyography (EMG) Evidence: Studies using surface EMG have demonstrated that jaw clenching significantly increases activity in the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscles. Conversely, slouched posture increases activity in the upper trapezius (uTP).8

- Reciprocal Tension: Tension in the SCM and trapezius pulls on the mastoid process and the occiput, altering the position of the cranial base and the mandible.

4.3 The Occlusal Consequence: The “Slide”

When the head is positioned forward, the hyoid bone is pulled deeply, creating tension on the suprahyoid muscles. This traction pulls the mandible posteriorly (back) and inferiorly (down).

- Retruded Contact Position: The lower jaw is pulled back.

- Premature Contact: When the patient tries to close their teeth, the mandible is further back than normal. The first point of contact is often the distal slopes of the posterior molars (second molars).

- The Slide: To fully close, the jaw must slide forward from this premature contact into Maximum Intercuspation (MI).

- The Damage: This slide creates a horizontal “skid” on the molars every time the patient swallows or clenches. This horizontal force is devastating to the cusps of the molars, shearing them off over time.

4.4 T-Scan Analysis of Postural Influence

Studies utilizing T-Scan III computerized occlusal analysis systems have quantified this effect. While traditional articulation paper only shows where the teeth touch, T-Scan shows when and with how much force.

- Study Findings: Research has shown that subjects with Forward Head Posture exhibit occlusal instability, characterized by an asymmetry index of occlusal force (AOF) and increased occlusion time (OT).9

- Implication: Instead of all teeth hitting simultaneously (which distributes force), the “Tech Neck” patient hits one or two molars first and hardest. These specific teeth take the brunt of the 250+ psi clenching force, leading to the high incidence of longitudinal fractures in second molars observed in clinics.10

5. The “Silver Tsunami”: Aging Dentition and Retention Rates

An intrinsic factor driving the increase in cracked teeth is the success of modern dentistry itself. Americans are keeping their teeth longer than ever before. This demographic shift, termed the “Silver Tsunami,” presents a paradox: the more teeth are retained into old age, the more “at-risk” inventory exists for fractures.

5.1 The Decline of Edentulism

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) illustrate a dramatic success story in public health that has created a new restorative challenge.

- 1999–2018 Trend: The age-adjusted prevalence of complete tooth loss (edentulism) among adults aged 65 and over declined significantly, dropping from nearly 30% to roughly 13%.11

- Current Status: As of 2020, only 12.9% of adults over 65 are edentulous. The vast majority retain a “functional dentition” (defined as roughly 20+ teeth).11

- Future Projections: The number of edentulous people in 2050 is predicted to be 30% lower than in 2010.13

5.2 The Structural Biology of Aging Teeth

While retaining teeth is positive for nutrition and quality of life, an 80-year-old tooth is structurally distinct from a 20-year-old tooth.

- Dentin Sclerosis: As teeth age, the dentinal tubules (microscopic channels in the tooth) become filled with mineral deposits (sclerosis). While this makes the tooth more resistant to cavities, it reduces the water content and elasticity of the dentin.

- Brittleness: The loss of moisture makes the tooth more brittle. Like an old branch compared to a green twig, an aging tooth is more likely to snap under load than to flex.14

- Stress History: A 70-year-old molar has undergone decades of “thermal cycling” (hot coffee followed by cold water) and millions of masticatory cycles. This accumulation of stress history lowers the threshold for fracture initiation.15

5.3 The “Endodontic Paradox” in the Elderly

A significant portion of retained teeth in the elderly have undergone root canal treatment.

- Loss of Proprioception: The dental pulp contains nerves that provide proprioceptive feedback—the sensation of how hard one is biting. When a tooth is root-canal treated, this internal feedback mechanism is lost.

- Unregulated Force: Elderly patients with root-treated teeth may subconsciously bite harder on those teeth because they lack the “warning system” of a live nerve. This, combined with the brittle nature of the non-vital dentin, significantly increases fracture risk.14

- Incidence Data: Research confirms a significant increase in cracked teeth incidence specifically in the over-60 age groups, particularly among males in 2021.1

6. Sleep Disordered Breathing: The Apnea-Bruxism Link

A critical and often overlooked “angle” in understanding tooth fractures is the relationship between sleep apnea and the destruction of dentition. Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) has reached epidemic proportions in the US, and its correlation with cracked teeth is becoming undeniable.

6.1 Prevalence of OSA (2015–2025)

The prevalence of OSA has been rising steadily, driven by obesity trends and an aging population.

- Current Estimates: Approximately 26% of adults aged 30–70 have at least mild OSA, with nearly 10% having moderate-to-severe disease.16

- Projections: By 2050, OSA is expected to affect nearly 77 million US adults, a 35% increase from 2020.18

6.2 The Mechanism: Bruxism as Airway Defense

For years, dentists believed bruxism was solely caused by stress or occlusal interferences. New sleep medicine research suggests that in many patients, sleep bruxism is a central nervous system reflex to maintain airway patency.

- Airway Collapse: In OSA, the soft tissues of the throat collapse during sleep, blocking oxygen flow.

- The Arousal Response: The brain detects the drop in oxygen and triggers a micro-arousal.

- Mandibular Advancement: To reopen the airway, the jaw muscles contract to thrust the mandible forward. This contraction manifests as clenching and grinding.

- The Damage: While this action aids breathing, it places destructive lateral forces on the dentition. The teeth become the “collateral damage” of the battle for oxygen.

6.3 Clinical Correlation

Studies show a statistically significant relationship between OSA and the presence of tooth fractures, particularly in patients aged 40 and older.19 Patients with OSA are frequently found to have cracked teeth, attrition (wear), and abfraction lesions (notches at the gumline caused by flexure).20

The rise in cracked teeth parallels the rise in undiagnosed sleep apnea. Dentists are increasingly recognizing that a split molar in a middle-aged male with a thick neck and a history of snoring is not just a dental problem, but a sign of a respiratory disorder.

7. Dietary Habits and Lifestyle Factors: The “Crunch” Culture

The changing American diet and specific lifestyle habits have introduced new mechanical risks to the dentition. The shift towards “healthy” snacking and the persistence of damaging habits like ice chewing have contributed to the fracture statistics.

7.1 The Rise of Hard Foods: The Almond Boom

Nutritional trends over the last decade have favored high-protein, low-carbohydrate, and plant-based diets (e.g., Paleo, Keto, Whole30). This has led to a massive increase in the consumption of tree nuts.

- Consumption Data: U.S. per capita almond consumption has increased at an annual rate of 5.5% since 2000. Between 2023 and 2024 alone, consumption rose nearly 6.5%.22

- Mechanical Hazard: Almonds, unpopped popcorn kernels, and granolas are notoriously hard. Research has identified “eating coarse foods” and “chewing on hard objects” as independent risk factors for cracked teeth.15

- The “Wedge” Mechanism: A hard nut acts as a fulcrum. When a patient bites down, the nut concentrates the entire bite force onto a small surface area of the tooth cusp. If that tooth has an existing micro-crack or a large filling, the nut acts as a wedge, driving the segments apart.

7.2 Pagophagia (Ice Chewing) and Anemia

A specific, damaging habit known as pagophagia (compulsive ice chewing) contributes significantly to fracture rates.

- Anemia Link: Pagophagia is often a symptom of iron deficiency anemia. The act of chewing ice is believed to trigger a vascular response that increases blood flow to the brain, providing a temporary alertness boost for anemic individuals.24

- Thermal Shock: Ice chewing subjects the tooth to extreme cold (contraction) followed by body temperature (expansion). This rapid thermal cycling induces thermal stress cracks in the enamel.

- Fracture Mechanics: The rigidity of ice requires significant force to fracture. Unlike food which softens as it is chewed, ice remains brittle until it shatters or melts. The impact force often exceeds the tensile strength of enamel, especially in teeth weakened by restoration.26

7.3 High-Protein Diets and Acidity

High-protein diets can also increase the acidity of the oral environment. The breakdown of proteins can lower oral pH, potentially leading to erosion of the enamel.27 Thinner, eroded enamel is less capable of absorbing shock, making the tooth more susceptible to fracture when hard objects are encountered.

8. Restorative Materials: The Amalgam vs. Composite Debate

The type of previous dental work present in the mouth is a significant predictor of fracture risk. The US is currently in a transition phase, phasing out dental amalgam (“silver fillings”) in favor of resin composites, but millions of legacy amalgam restorations remain.

8.1 The “Wedging” Effect of Amalgam

Dental amalgam has been the standard for posterior restorations for 150 years. However, its mechanical properties contribute to late-stage tooth fractures.

- Lack of Adhesion: Amalgam does not bond to the tooth. It is held in place by “mechanical retention”—undercuts drilled into the tooth. This removal of healthy tooth structure to create the lock undermines the cusps.

- Thermal Expansion: Amalgam has a higher coefficient of thermal expansion than tooth structure. Over decades of hot/cold cycles, the metal expands and contracts at a different rate than the tooth, acting as a slow-motion wedge.

- Fracture Patterns: Retrospective studies indicate that amalgam restorations are associated with distinct fracture patterns, particularly when wear facets are present.28

8.2 Composite Resin: Polymerization Shrinkage

Modern dentistry relies on bis-GMA composite resins. While these materials bond to the tooth and can reinforce the structure, they introduce a different stress: polymerization shrinkage.

- Shrinkage Stress: When composite cures (hardens), it shrinks by 2-3%. In a large restoration bonded to multiple walls of a tooth, this shrinkage pulls the cusps inward, creating constant tension (cuspal deflection) even when the tooth is not in function.

- Durability and Failure: Historical data suggested composites failed more often than amalgams. However, “Big Data” studies (2014–2021) involving over 650,000 patients now indicate that composite restorations demonstrate lower replacement rates (11.98% failure) compared to amalgams (17.49% failure) in some populations.29 This suggests that while composites have issues, the phase-out of amalgam may actually reduce fracture rates in the long term, though the transition period involves replacing many failed amalgams that have already cracked the tooth.

8.3 The “Death Spiral” of the Tooth

The current wave of fractures often involves teeth that entered the “restorative cycle” 10–20 years ago.

- Teen years: Small cavity, small filling.

- 30s: Filling fails, replaced with larger filling.

- 40s/50s: The remaining tooth structure is thin. The patient develops “COVID Clench” or sleep apnea.

- Event: The tooth fractures.

This cycle explains why the 40-60 age demographic is the epicenter of the fracture epidemic. They are at the point in the tooth life-cycle where structural integrity is minimal, just as their life stress is maximal.

9. Clinical Diagnosis and Management: Insights from the NDPBRN

Quantifying cracked teeth is challenging because “cracked tooth” is a clinical finding, not always a clear-cut diagnosis like a cavity. The National Dental Practice-Based Research Network (NDPBRN) has conducted extensive registries to map this territory.

9.1 The NDPBRN Cracked Tooth Registry

The NDPBRN registry provides the most granular data on the clinical presentation of cracked teeth in the US.30

- Prevalence: In a survey of molars, 31.4% had at least one crack, and 66.1% of individuals had at least one cracked molar. This indicates that cracks are ubiquitous; the challenge is determining which ones will progress to failure.

- The “Stained Crack” Paradox: Interestingly, cracks that were stained (dark lines) were negatively associated with symptoms.32 A stained crack is often an old, stabilized crack that has filled with organic debris. The dangerous cracks are often clean, invisible hairline fractures that flex under pressure.

- Predictors of Treatment: The presence of a crack detectable with an explorer or one that blocked transilluminated light strongly predicted a recommendation for a crown (OR=1.6 to 1.8).33

9.2 Symptomatology

The classic presentation of a cracked tooth is erratic pain.

- Cold Sensitivity: The NDPBRN study found that pain to cold (37%) was more common than pain to biting (16%).34 This contradicts the traditional teaching that “pain on release of biting” is the hallmark of a crack. The cold sensitivity arises because the crack allows fluid movement within the dentinal tubules, stimulating the pulp.

- The “Jolt”: Patients often report a sharp, electric-shock sensation when hitting a specific spot on the tooth (e.g., eating a seeded bread).

9.3 Treatment Outcomes and Prognosis

Historically, deep cracks involving the root were considered hopeless and extracted. Recent data (2015–2025) has shifted this paradigm.

- Survival Rates: New studies involving datasets of deeply cracked teeth show that if treated with a crown (to bind the segments together) and root canal therapy (if the nerve is involved), survival rates range from 82% to 96% over 2-4 years.35

- The Critical Factor: The prognosis depends heavily on periodontal probing depth. If a crack has caused a deep pocket (narrow defect) alongside the root, the prognosis drops significantly.36

This shift in data means that while the incidence of cracks is up, the rate of tooth loss due to cracks may not rise as steeply, provided patients seek timely care and receive crowns rather than extractions.

10. Conclusion and Future Outlook

The “epidemic” of cracked teeth in the United States observed between 2015 and 2025 is not a statistical artifact but a genuine public health trend driven by a convergence of biological, environmental, and behavioral factors.

10.1 Synthesis of Factors

- The Trigger: The COVID-19 pandemic acted as a potent psychological stressor, triggering widespread bruxism (the “COVID Clench”) in a population already predisposed to anxiety.

- The Substrate: An aging population retaining heavily restored teeth provided the “brittle” material necessary for fractures to occur. The success of cavity prevention in youth has led to the challenge of fracture prevention in old age.

- The Mechanics: The shift to home offices deteriorated posture (“Tech Neck”), altering occlusal forces and concentrating stress on posterior teeth via the SCM/Trapezius kinetic chain.

- The Lifestyle: High-stress lifestyles, combined with diets rich in hard foods (almonds, ancient grains) and habits like ice chewing, increased the frequency of “wedging events.”

- The Underlying Pathology: The rising prevalence of sleep apnea drives nocturnal bruxism as a survival mechanism, destroying teeth in the process of maintaining the airway.

10.2 Future Implications

As the “Silver Tsunami” continues and the workforce remains hybrid (perpetuating ergonomic challenges), the incidence of cracked teeth is unlikely to recede to pre-2015 levels. The “cracked tooth” is replacing the cavity as the defining challenge of adult restorative dentistry.

Future management will likely shift from reactive (crowning a broken tooth) to preventive. This includes the increased prescription of prophylactic night guards (occlusal splints), the screening of dental patients for sleep apnea, and the education of patients regarding the “dietary biomechanics” of hard foods. The data suggests that dentistry must evolve from treating the hole in the tooth to treating the load on the tooth.

Key Data Summary Table

| Factor | Key Metric / Finding | Source |

| Endodontic Vol. | 2x increase in cracked teeth (Sept 2020 vs 2019) | 1 |

| Bruxism | 71% of dentists reported increase (2021) | 2 |

| Search Trends | +13% Google Search volume for “Cracked Teeth” (US) | 3 |

| Demographics | Peak incidence in ages 40–60; shift to males in 2021 | 1 |

| Material Failure | Amalgam failure rate ~17.5% vs Composite ~12% | 29 |

| Sleep Apnea | 35% projected increase in OSA by 2050 | 18 |

| Edentulism | Dropped to ~12.9% (Ages 65+), increasing at-risk teeth | 11 |

| Almond Consumption | +5.5% annual growth since 2000 | 23 |

Works cited

- Cracked Teeth and Vertical Root Fractures: A New Look at a Growing Problem – American Association of Endodontists, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.aae.org/specialty/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/12/ecfe-2022-edition-FINAL.pdf

- HPI poll: Dentists see increased prevalence of stress-related oral …, accessed January 11, 2026, https://adanews.ada.org/ada-news/2021/march/hpi-poll-dentists-see-increased-prevalence-of-stress-related-oral-health-conditions/

- Increased burden of Cracked Teeth in US and UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from an infodemiological analysis – ResearchGate, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/367340137_Increased_burden_of_Cracked_Teeth_in_US_and_UK_during_the_COVID-19_pandemic_evidence_from_an_infodemiological_analysis

- Incidence of Cracked Teeth Before, During, and After the Covid‐19 Pandemic—A Retrospective Analysis in a German Private General Practice – PMC – NIH, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12502617/

- Cracked Teeth and Vertical Root Fractures in Pandemic Crisis … – NIH, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11447506/

- New research on oral health care during the COVID-19 pandemic – Delta Dental, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.deltadental.com/us/en/about-us/press-center/2023-press-releases/new-research-from-delta-dental-finds-a-significant-decrease-in-the-provision-of-preventive-oral-health-services-resulting-from-the-pandemic.html

- TMJ Disorder and Work-From-Home: How Your Home Office Setup Could Be Causing Jaw Pain | Family Dentist in Las Vegas, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.dentistsoflasvegas.com/blog/home-office-setup-could-be-causing-jaw-pain

- Effects of sitting posture and jaw clenching on neck and trunk muscle activities during typing, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33492675/

- Influence of the Text Neck Posture on the Static Dental Occlusion – PMC – NIH, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9501254/

- (PDF) Influence of the Text Neck Posture on the Static Dental Occlusion – ResearchGate, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/363641406_Influence_of_the_Text_Neck_Posture_on_the_Static_Dental_Occlusion

- Prevalence of Tooth Loss Among Older Adults: United States, 2015–2018 – CDC, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db368.htm

- Epidemiology of oral health in older adults aged 65 or over: prevalence, risk factors and prevention – NIH, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12185596/

- Projections of U.S. Edentulism Prevalence Following 5 Decades of Decline – PMC, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4212322/

- Why Are Seniors At Risk For Breaking Teeth? – Pascack Dental Arts, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pascackdental.com/why-are-seniors-at-risk-for-breaking-teeth/

- Cracked Teeth and Poor Oral Masticatory Habits: A Matched Case-control Study in China – PubMed, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28416310/

- The Global Burden of Obstructive Sleep Apnea – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12071658/

- Rising prevalence of sleep apnea in U.S. threatens public health, accessed January 11, 2026, https://aasm.org/rising-prevalence-of-sleep-apnea-in-u-s-threatens-public-health/

- Obstructive Sleep Apnea Expected to Affect Nearly 77 million U.S. Adults by 2050, New Resmed Study Finds, accessed January 11, 2026, https://newsroom.resmed.com/news-releases/news-details/2025/Obstructive-Sleep-Apnea-Expected-to-Affect-Nearly-77-million-U-S–Adults-by-2050-New-Resmed-Study-Finds/default.aspx

- Frequency of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Patients Presenting with Tooth Fractures: A Prospective Controlled Study – PubMed, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36661888/

- The Connection Between Sleep Apnea and Broken Teeth – Atlanta Smiles, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.atlantasmiles.com/the-connection-between-sleep-apnea-and-broken-teeth/

- Sleep Apnea’s Impact on Oral Health | Savannah, GA | Medical Arts Dentistry, accessed January 11, 2026, https://medicalartsdentistry.com/sleep-apneas-impact-on-oral-health/

- May 2025 Almond Market Report – Select Harvest USA, accessed January 11, 2026, https://selectharvestusa.com/news-resources/market-reports/may-almond-market-report

- US Almond Production and Consumption Trends – Agricultural Economic Insights, accessed January 11, 2026, https://aei.ag/overview/article/united-states-almond-production-consumption-trends

- Why Chewing Ice Is Bad for Your Teeth – Cleveland Clinic Health Essentials, accessed January 11, 2026, https://health.clevelandclinic.org/chewing-ice-bad-for-teeth

- The Dangers of Chewing on Ice | Dentist in Barton City | Jewel Lake Dental, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.healthysmilesbartoncitydentist.com/blog/2021/07/07/dangers-of-chewing-ice-emergency-dentist-barton-city/

- Chewing Ice Can Ruin Your Teeth – Parma Heights OH | Dr. Carrie Hansen DDS, accessed January 11, 2026, https://drcarriehansendds.com/2025/05/14/chewing-ice-can-ruin-your-teeth/

- Too Much Protein? Your Diet and Your Dental Health – Adam Brown DDS, accessed January 11, 2026, https://adambrowndds.com/too-much-protein-your-diet-and-your-dental-health/

- Association between dental fracture and amalgam restoration: a case-control study – PMC, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12014111/

- Survival Rates of Amalgam and Composite Resin Restorations from Big Data Real-Life Databases in the Era of Restricted Dental Mercury Use – MDPI, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.mdpi.com/2306-5354/11/6/579

- Study Highlights: Dental Practice-Based Research Networks | NIDCR, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/research/clinical-trials/national-dental-practice-based-research-network/study-highlights-dental-practicebased-research-networks

- Cracked Teeth Registry, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.kpchr.org/ndpbrn/public/pages/meetings/assets/2013-AnnMtg/Cracked_Teeth_Registry-Tom_Hilton-Jack_Ferracane.pdf

- Correlation between symptoms and external characteristics of cracked teeth: Findings from The National Dental Practice-Based Research Network – PubMed, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28160942/

- Recommended treatment of cracked teeth: Results from the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network – PubMed Central, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7172112/

- Lessons Learned from the Cracked Tooth Registry – a Three-year Clinical Study in the Nation’s Network – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10686254/

- Cracked Teeth: To Treat or Not to Treat? – American Association of Endodontists, accessed January 11, 2026, https://www.aae.org/specialty/cracked-teeth-to-treat-or-not-to-treat/

- 12-month Success of Cracked Teeth Treated with Orthograde Root Canal Treatment – PubMed, accessed January 11, 2026, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29429822/

60 DAY warranty on all custom-made products | 1,000+ 5 Star ★★★★★ Reviews

60 DAY warranty on all custom-made products | 1,000+ 5 Star ★★★★★ Reviews